November 1833. Daniel Muir, an army recruiting sergeant who had settled in Dunbar as a meal dealer some 4 years earlier, married his second wife, 20 year old Ann Gilrye, daughter of local flescher and local councillor, David Gilrye. The couple lived in a room behind Daniel’s shop on the west side of Dunbar High Street.

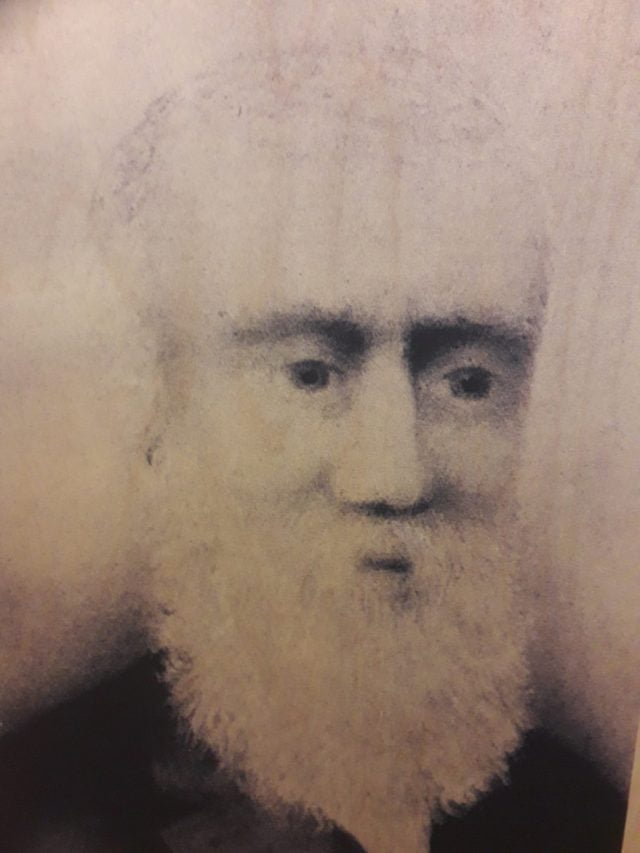

Daniel Muir

Daniel’s parents had both died when he was very young, and he moved to Crawfordjohn, Lanarkshire to be raised by his sister. He joined the army at a young age, and received several postings, ending up as a recruiting sergeant in Berwick. It was here he was introduced to a young Helen Kennedy, who had inherited her late mother’s meal dealership in Dunbar. The pair married in 1829 and Daniel took over the business. Sadly Helen died in 1832. Some sources report a child in the marriage, however there are no official records of this, there being every chance both Helen and the baby died.

Daniel mourned his wife and grew both the business and his own standing in Dunbar society. Only a few yards away across Dunbar High Street, a young Ann Gilrye lived with her family above her father’s butcher’s shop. Ann caught Daniel’s eye, and the pair were married in November 1833. Their first daughter, Margaret was born in 1834, followed by Sarah in 1836, and their first son, John Muir in 1838. They would go on to have 8 children in total, all of whom survived to adulthood.

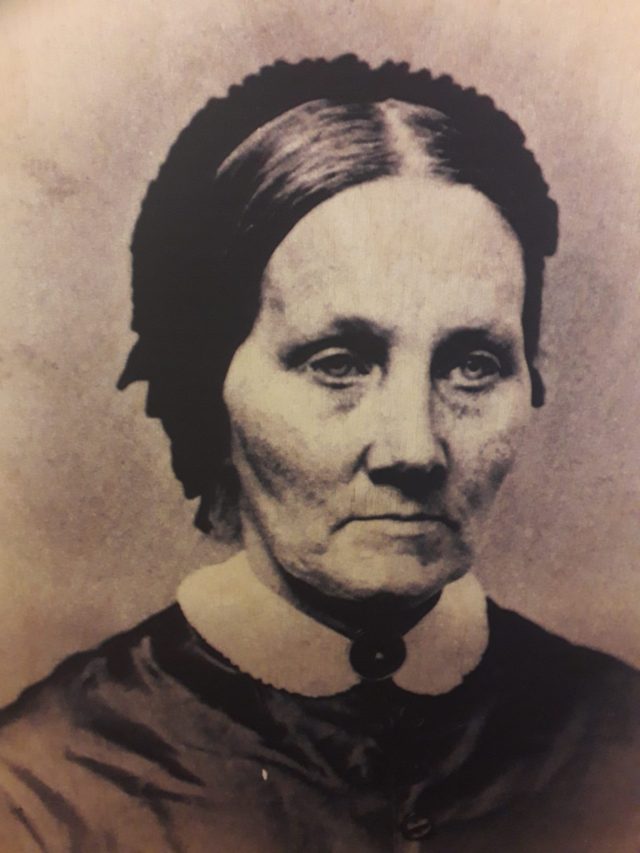

The Gilrye family had also experienced tragedy, Ann and her sister, Margaret were the only surviving

Ann Gilrye Muir

siblings from a family of 8. There can be no doubt that the loss of so many of his own children led to David Gilrye’s desire to be close to his grandchildren. John remembers walks with his grandfather in ‘The Story of My Boyhood and Youth’, crediting him with first awakening his love of nature, and with teaching him to read from the shop signs on the High Street.

My earliest recollections of the country were gained on short walks with my grandfather when I was perhaps not over three years old. On one of these walks grandfather took me to Lord Lauderdale’s gardens, where I saw figs growing against a sunny wall and tasted some of them, and got as many apples to eat as I wished. On another memorable walk in a hayfield, when we sat down to rest on one of the haycocks I heard a sharp, prickly, stinging cry, and, jumping up eagerly, called grandfather’s attention to it. He said he heard only the wind, but I insisted on digging into the hay and turning it over until we discovered the source of the strange exciting sound–a mother field mouse with half a dozen naked young hanging to her teats. This to me was a wonderful discovery. No hunter could have been more excited on discovering a bear and her cubs in a wilderness den.

One can only imagine David Gilrye’s emotions in 1849, when Daniel announced he was following his religious inclinations and taking his wife and children to America to start a new life.

Now that the nights are getting darker and the leaves are turning, it’s time for us to switch to our winter opening hours. We will be open 10am – 5pm (last entry 4pm) Wednesday – Saturday. We will be closed Sunday – Tuesday each week.

In these strange times when we are being encouraged to stay close to home, it is the perfect time to spend quieter months visiting places on your doorstep that you’ve always meant to see but never quite got around to it! We also have locally made gift ideas that might not be available from online retailers. Lots of reasons to pop in, we look forward to welcoming you.

We love the recently launched Dunbar Art Trail, which features the John Muir Statue on Dunbar High Street, and the John Muir Stone in Lochend Woods.

The Dunbar Art Trail provides a great way to explore Dunbar, via all the public artworks dotted around the town. With an in depth history and information about the artworks, the artists behind them and an interactive map, this is a great free to use tourist map ideal for a socially distanced adventure!

The Dunbar Art Trail provides a great way to explore Dunbar, via all the public artworks dotted around the town. With an in depth history and information about the artworks, the artists behind them and an interactive map, this is a great free to use tourist map ideal for a socially distanced adventure!You may remember that earlier in the summer we published David Anderson’s research into the buildings on Dunbar High Street occupied by the Muirs. There were tales of commerce, double-crossing and greed, as we discovered that the buildings had nearly as interesting a story to tell as John Muir himself!

We are delighted that the series of blogs has now been gathered into an online exhibition and can be enjoyed once again at your leisure! You will find Muir Houses Through Time on our Exhibitions page in bitesize chunks for you to browse.

John Muir’s Birthplace has announced it has been recognized as a 2020 Travellers’ Choice award-winner for attractions. Based on a full year of Tripadvisor reviews, prior to any changes caused by the pandemic. Winners are known for consistently receiving great traveller feedback, placing them in the top 10% of hospitality businesses around the globe.

Duncan Smeed, Chair of the John Muir Birthplace Charitable Trust said: “On behalf of the partner Trustees of John Muir Birthplace Charitable Trust – Dunbar Community Council, East Lothian Council, Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace and the John Muir Trust – I am delighted that the hard work and planning that goes into the staffing and resourcing of the Birthplace has been recognised by the this Tripadvisor’s 2020 Travellers’ Choice Award. Comments by visitors to the Birthplace are invariably very positive and highlight the very warm welcome they receive from the Birthplace staff and volunteers and the inspiring nature of the exhibits that tell the story of Muir’s life and legacy. Earlier this year saw the arrival of the 200,000th visitor and the Birthplace is undoubtedly a major contributor to the vibrancy of Dunbar High Street. This Travellers’ Choice Award will be a major boost to the efforts to promote Dunbar as a destination of choice for visitors – both local and from afar.”

“Winners of the 2020 Travellers’ Choice Awards should be proud of this distinguished recognition,” said Kanika Soni, Chief Commercial Officer at Tripadvisor. “Although it’s been a challenging year for travel and hospitality, we want to celebrate our partners’ achievements. Award winners are beloved for their exceptional service and quality. Not only are these winners well deserving, they are also a great source of inspiration for travellers as the world begins to venture out again.”

About John Muir’s Birthplace

Discover how the boy born in this house became one of the driving forces behind the modern conservation movement. The exterior has been restored to its original condition. Inside, you’ll find a warm welcome with friendly, well informed staff always available to answer questions. Our absorbing interpretation centre will take you on the journey of John Muir’s life as a pioneering conservationist, explorer, writer, geologist and inventor. The building is fully accessible with three floors of family friendly displays complemented by a lively exhibition and events programme and a shop offering books and gifts for all ages.

To see traveller reviews and popular features of John Muir’s Birthplace visit John Muir’s Birthplace on Tripadvisor.

Although we are now open to the public, we appreciate that there are fans of John Muir who are unable to visit us due to travel and other restrictions. We are therefore continuing our drive to provide more of our past exhibitions online.

We have now added John Muir and Geology to the list. John Muir and Geology explores the Scottish heroes who helped unravel Dunbar’s geological story. This exhibition was first shown in 2017 during the Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology.

The exhibition will also be promoted as part of the Scottish Geology Festival 2020 which will offer a range of events and activities for anyone interested in geology; there will be fantastic opportunities for all to get involved, including families, communities and tourists visiting the area. More on the festival can be found on the Scottish Geology Trust Website.

We are delighted to have achieved our ‘We’re Good to Go’ Accreditation in time for reopening tomorrow, Tues 18 August. We have some new procedures in place to ensure our visitors and staff can be confident they are safe when in our Museum.

• Please maintain social distancing, follow directional signage, use the hand sanitiser or wash your hands regularly and wear a face covering at all times in the Museum (unless exempt).

• Please do not visit if you or anyone in your household has any symptoms of Coronavirus.

• We have removed some of the activities and interactives from our museums to protect visitors and staff & have an enhanced cleaning regime in place.

• We have sneeze screens at desks, hand sanitising stations and one way systems around the museum.

• Payment by credit or debit card in our shop is preferred

• Please book your free visit in advance by calling 01368 865899 or email museumseast@eastlothian.gov.uk. This will help to maintain social distancing within our building.

Please be prepared to leave a contact name and number for your party, as we are taking part in the Scottish Government ‘Test and Protect’ Scheme. Details will be kept secure for 21 days and then destroyed, they will not be passed on to any 3rd party.

We look forward to welcoming you all tomorrow!

One week to go!

We are really gearing up to start welcoming you back to John Muir’s Birthplace from Tuesday 18 August. Our screens have now been installed to keep both visitors and staff safe, and we will be laying floor stickers to help with social distancing. We are also working closely with our staff this week to devise new cleaning regimes, and we recommend that anyone wishing to visit to prebook their time by emailing museumseast@eastlothian.gov.uk or calling 01368 865899 as we will be limiting the amount of people in the building at one time.

Our opening times from 18 August will be Tuesday – Saturday 10am – 5pm – we can’t wait to welcome you back!